When I think of westerns a few things come to mind. Vast landscapes dotted with dwarfed trees or surreal cactuses, dusty streets lonely of people but not tumbleweeds, Buffalo, a sky so blue and wide there seems to be almost nothing else, Indians, and of course, the hero, whose energy conserving laziness, whose smooth slouch, has permeated almost every pore of globalized society.

But there is also a dream to the version of West we’ve all learned about while watching Clint Eastwood’s cigar roam from one corner of his mouth to the other. A dream of possibility, of unlimited potential for success, and of untouched wilderness whose fruits could be anything.

Hueco Tanks’ West Mountain can be kind of a hike, depending on what boulder problems you want to climb on. After climbing Diaphanous Sea my fingers were raw and bruised; I needed to rest them for at least a couple of days. So when Matt, Cory and Ryan all decided to pack light and climb The Round Room, 1969, Best of the West, Crash Dummy, and Star Power in a day, I left my extra shoes and pad behind and followed. All I really wanted to do was climb The Round Room, whose easy traverse circles a room with hueco’d walls and a damp dirt floor that always smells of water. The Round Room is a quintessential Hueco Tanks feature, and even though I’ve been climbing there for six years, it took until now to make it all the way out to the remote end of West Mountain.

We dropped our pads under a big oak at the beginning of a stone ramp and scrambled up with chalk and water. Going to The Round Room can feel like time travel, if you want it to. That little compartment in the earth with nothing but a small patch of sky for ceiling seems unchanged. It could be 1880, and the great mythic westerner could be lazily riding by. The only time in a place like The Round Room is in the hands of your watch and in the number of times you’ve traversed its entirety.

|

| The Round Room |

After a few laps and a posed picture of all of us clinging to the wall and smiling awkwardly, we slid back down the ramp to our pads in the shade and ate candy bars and trail mix. The sun shined with the precision of a flashlight through the bare branches and I could feel its warmth on my skin.

“Here are some pottery shards,” Cory said as he picked up a small, broken piece of clay. He turned it over and over in his chalky fingers. I could see its jagged broken edges, the gentle curve of its former shape back when it was something more than an ancient piece of discarded waste slowly chipping away from all our footsteps and becoming nothing but dirt. “These things are everywhere,” he said and put it back down where it came from.

In Matt Wilder’s guidebook to Hueco Tanks there’s a picture of himself hanging open-handed on some cool looking slopers. 1969 gets just two stars but it’s one of those problems that people always talk about. “We’re going there tomorrow, they say at the fire,” as if the approach is like walking to the corner for a cup of coffee. Anyone who knows any better rolls their eyes and asks who their guide is.

It’s impossible to actually walk to 1969. The approach is one that involves technical face climbing, even some chimneying. Going to 1969 isn’t like walking downtown, it’s like discovering an entirely different world hidden in a dangerous maze, it’s like that scene in The Last Crusade, where Indiana has to figure out a bunch of booby traps to get to the Holy Grail as an army of cold eyed Nazis hold his friends at gunpoint.

1969 is not the Holy Grail, It’s a lowball on good rock way the fuck back in the heart of West. Unless you’re spending a great deal of time in Hueco and have run out of other things to climb, don’t haul your crash pads back there.

We decided to leave our pads with Ryan, whose climbing skills weren’t high enough for the you-fall-you-die approach, and scrambled up the gully leading, eventually to that problem so romantically pictured in the guide. Past a vertical face and through a narrow gap between walls the gully opened up. Walls of bulging stone overhung a few tall, jagged boulders like suddenly frozen waves. Two or three small oaks, their branches just starting to bud green, clung to life, thrived. The path led us under giant roofs and boulders, their bellies stained that flaming white, to red to deep, rotten wood brown by the often present but rarely seen flow of water. Its swirling fingerprint is everywhere in the cosmic shapes the rock in Hueco has taken after so many centuries of persistent effort. Water has drawn so much to Hueco, it’s even responsible for all those climbers living in tents and examining their fingertips too closely on their rest days.

After half an hour of crawling under rocks big as train cars, we find 1969. My fingers are still sore from climbing the day before, and the sloping pockets of the boulder problem feel threatening. We talk about coming back on our last day, but West Mountain isn’t the kind of place you go to get a lot of climbing in, it’s a place you go to walk around, peek into dark holes and narrow gullies because West continues to give. Every corner has probably been explored. Someone has stuck their head in every dark hole and let their eyes adjust, but finding lines, cleaning and climbing them takes a kind of creativity and motivation many don’t have. Still, problems like the 130 foot long NRA, only climbed last year, are still lurking deep in the mountain.

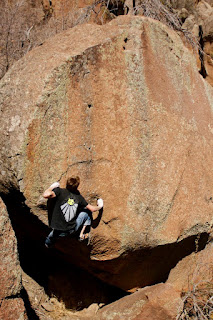

|

| Cory on Best of the West |

Once we’d retrieved our pads and Ryan, we staggered and sweated our way up to The Best of West, a problem that ironically doesn’t ever really top out. Still, this was the highest up West Mountain I’d ever been. We went over to look at The Feather, a problem I’d wanted to try since I first saw a picture of it. Every other mountain seemed like it was just a few hundred yards away. We could see people carrying pads and we could hear the grunts and yells of unnecessarily loud climbers over on North Mountain. I’ve always felt that West, from those more popular places, seemed like it was miles away, foreign and unknown. And from its top everything else seemed tame and boring, picked over like a market after the 6 PM rush. But the top of West, or the near top, felt like a place I could just sit and watch the clouds rush by without some enormous group coming by with thirty pads and screams to wake the dead.

|

| The Feather |

After climbing Best of the West and trying The Feather, (I was able to do it from a stand start) we hike back down the side of West and over to Star Power, A long roof of giant huecos and jugs. Star Power is one of my favorite climbs in Hueco, it’s like the famous Nobody Gets Out of Here Alive on North Mountain, but three times as long and a bit harder. We all run a quick lap, then move over to Crash Dummy, another favorite.

|

| Matt on Crash Test Dummy |

Coyotes start to yip and howl across the field at the base of North Mountain. They scream and cry and as we all look, trying to pick them out against the brown rock, suddenly stop. We never saw them.

As we walked back to the car I thought about the day. I thought of The Round Room, time, the smell of damp soil, and pottery shards I thought of the gully to 1969 and the feeling of possibility around every next corner. I thought of the near top of West, The Feather, and the distance I felt between the rest of the world and myself. As the coyotes found something else to get excited about and as I unlocked my truck, I thought of the great mythic West and that there was no other name better for where we’d just been than West Mountain.